Alternative Proteins career guide

Written by

Linne van der Meulen

Overview

Cause area: factory farming

- Scale: High

- Neglectedness: High

- Tractability: Medium

Factory farming: why pressing?

Factory farming is a major, if not leading cause, of many of the world’s most pressing global challenges. First and foremost, it severely impacts animal welfare. The scale of suffering is unmatched by other cause areas. Each year, over 75 billion land animals and more than a trillion fish are slaughtered for human consumption [1]. To put this in perspective, 75 billion is ten times the size of the current global human population. This is nearly as much as all the people who ever lived. More animals are killed for food production each day (221.6 million excluding fish [2] and shrimps [3]) than the total number of people killed in all wars throughout history [4].

This scale of killing is a result of technological advancements and industry concentration. This enabled fewer but larger farms to operate with increased efficiency. Conditions for these animals are often dire, with over 90% housed in intensive systems that prioritise economic efficiency over animal welfare [5]. This has led to a variety of health and welfare issues, including organ failure, injuries, inability to express natural behaviour, and high mortality rates. All species of farmed animals face their own distinct set of hardships. Over 70% of the 24 billion chickens alive today live in crowded and uncomfortable conditions on intensive farms. These chickens have been bred to grow so fast, they struggle to carry their own weight and many suffer from leg deformities. They live in large, dense groups where they sometimes hurt or even cannibalise each other. To prevent this, their beaks are often trimmed when they’re young. Similar practices are common with pigs, who are housed so densely that they regularly injure each other out of frustration. In prevention, piglets are usually tail-docked and have their teeth ground down.

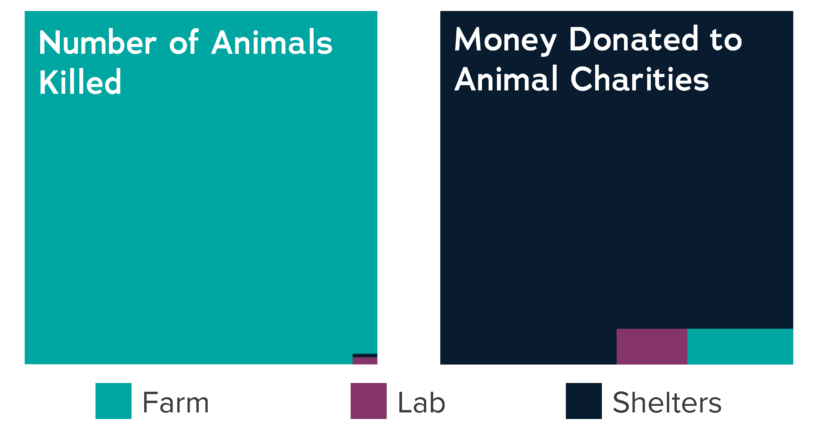

Understanding these numbers and the depth of suffering is crucial to understand why caring about animal welfare is important. The reality is that billions of animals worldwide live brief, confined, and commodified lives. The question of how to appropriately weigh the lives and suffering of animals against those of humans is often raised. A key point of consensus here is that sentience —the capacity to feel pain and joy – matters. Some argue that consciousness is also morally relevant. Current literature suggests that farmed animals are probably conscious, albeit potentially not to the same extent as humans. Given this, even if farmed animals were to be attributed just a fraction, say 5%, of the moral weight compared to humans, the numbers still paint a grim picture. Therefore, regardless of the exact moral weighting, the scale of suffering in factory farming makes it a profound and neglected ethical concern. In the US, around 97% of philanthropic funding is directed towards human-related causes. The remaining 3% is divided between animal welfare and environmental issues. Within this funding spent on animal welfare, only 1% is dedicated to farmed animals, despite them making up over 99.6% of domesticated animals [6].

Figure 1: Spending of donations to animal charities in the US. Source, ACE [7]

Beyond animal welfare concerns, animal agriculture is also a major driver of environmental issues. Accounting for 14.5-20% of global greenhouse gas emissions [8], it exceeds the total emissions from the transportation sector [9]. Additionally, animal agriculture is a major contributor to nitrogen pollution, primarily through the release of ammonia from manure. In the Netherlands, this has led to serious concerns about air and water quality, as well as the health of natural ecosystems. Livestock farming is the largest single contributor to biodiversity loss, mainly through deforestation. As an extremely inefficient system of food production, land use is at the heart of this issue [10]. While animal agriculture occupies 80% of global agricultural land, it only yields 18% of our calories. For this reason, it also poses a threat to food security. Antibiotic resistance and zoonotic diseases (including pandemic risks) pose additional global health risks [11]. With global meat consumption projected to increase by 70 to 100% by 2050, these issues are only set to intensify [12]. Reforms in our agricultural and food system are urgently needed.

What are alternative proteins and why are they important?

Alternative proteins are proteins produced from plants, animal cells, or by way of fermentation. Some of these products are available to consumers today, including numerous plant-based and fermentation-derived options. Others, such as cultivated meat, remain primarily in development. Compared to conventional animal products, alternative proteins require fewer inputs, such as land and water, and generate far fewer negative externalities, such as greenhouse gas emissions [13]. Additionally, the advances in alternative proteins – particularly in technologies that enable protein production using solar power, CO2, and hydrogen as feedstock – present opportunities for existential risk reduction. Such innovative approaches could revolutionise food production by fully eliminating the need for agricultural land.

Despite decades of advocacy to raise awareness of the negative impacts of factory farming, meat consumption remains steady [14]. This shows changing what we eat is tough, and a lot depends on having good options to switch to. Enter alternative proteins: they offer people the products they like to eat without the environmental and animal welfare costs. Alternative proteins may be the only solution that doesn’t require consumer sacrifice. Right now, these alternatives aren’t quite there yet in terms of price, taste, convenience, and nutrition. We expect that reaching this will be a key milestone in ending factory farming.

The Netherlands as rising global leader in alternative proteins

The Netherlands is particularly well positioned to be a global leader in the development of alternative proteins, thanks to a range of factors. Central is its innovative agricultural sector, known for its technological innovation and efficiency. The Netherlands also has strong research institutions in food science and agricultural research. The Dutch government is listed behind Singapore as having the second strongest commitment to their alternative protein sector. In its commitment to achieving its climate goals, the Dutch government has made substantial investments aimed at reducing livestock farming and fostering a cellular agriculture ecosystem. In 2021, a €25 billion initiative was announced to reduce livestock numbers by a third. Following this, the Dutch government invested an unprecedented €60 million in cellular agriculture in 2022. This funding was part of the implementation of the National Protein Strategy and marks the largest single investment in cellular agriculture by any government worldwide [15].

The Netherlands has a strong alternative protein ecosystem, supported by a unique “quadruple helix” collaboration, bringing together industry, academia, government, and the public. Various consortia and initiatives such as Foodvalley NL, Green Protein Alliance, The Protein Community, and Cellular Agriculture Netherlands enjoy government support [16]. In the academic landscape, Dutch universities play a crucial role in advancing alternative protein research. Wageningen University and Research (WUR), renowned for its focus on agriculture, environment, and food sciences, is actively engaged in alternative protein research. There are also active research and student groups on alternative proteins at other Dutch universities such as Utrecht, Maastricht, Delft, and Leiden.

While the Netherlands is pioneering in its approach to alternative proteins, it faces challenges within the broader regulatory environment of the European Union. The regulation of novel foods has made it difficult for new alternative protein products to enter the EU market. As of today, cultivated meat and products with precision fermentation-derived ingredients are still awaiting approval. Despite these challenges, the Netherlands is showing strong commitment to alternative proteins. In 2022, they made a significant move by allowing controlled tastings of lab-grown meat, as decided by the Dutch House of Representatives [17].

Current state and what is most needed

Working to advance the development and adoption of alternative proteins is probably one of the highest impact careers in terms of ending factory farming. Because of the reasons described above, careers in the Netherlands may be especially high impact. The current state and key bottlenecks for alternative proteins depend on the innovation area and geographical location. If you’re completely new to the space, consider checking out GFI’s introduction to alternative proteins.

- Plant-based products are already produced at scale and often at price parity with conventional animal products, yet are lacking in taste. Hybrid products offer potential to improve the taste and texture of conventional plant-based products. Hybrid products are a blend of plant-based ingredients with cultivated meat or with for example specific enzymes produced through precision fermentation.

- Cultivated meat is produced by growing real animal cells in a controlled environment, mimicking the tissue formation in living animals. This technology shows a lot of promise as it can produce real meat, without needing to raise or slaughter animals. This is still at the prototype stage however, with research and development (R&D) being the major hurdle. Hybrid products with plant-based ingredients look promising because they presumably face less R&D and manufacturing challenges. Regulatory barriers will also become significant once these products are ready for the market in the EU. Singapore is the first (and at this point in time, the only) country to approve commercial sale of cultivated meat.

- Precision fermentation uses genetically modified microorganisms, such as yeast or bacteria, to produce specific functional ingredients. This technology is also used to make insulin for diabetic patients and rennet for cheese. In the alternative protein sector, precision fermentation can be used to produce specific proteins, enzymes, or fats that are typically derived from animals. Precision fermentation is promising, particularly in enhancing plant-based products to achieve taste parity with animal-sourced foods. It could also produce essential growth proteins for cultivated meat, currently a significant cost factor in its production. Challenges for precision fermentation include scaling up manufacturing capacity and navigating regulatory landscapes, especially in the EU where it intersects with GMO regulations.

- Biomass fermentation uses the rapid growth of microorganisms to efficiently make large amounts of protein-rich food. Here, the reproducing microorganisms themselves are the main ingredients for alternative proteins. Biomass fermentation is more advanced in development than precision fermentation and cultivated meat, with the ability to produce at scale, as seen with products like Quorn. Scaling up manufacturing capacity remains a primary bottleneck.

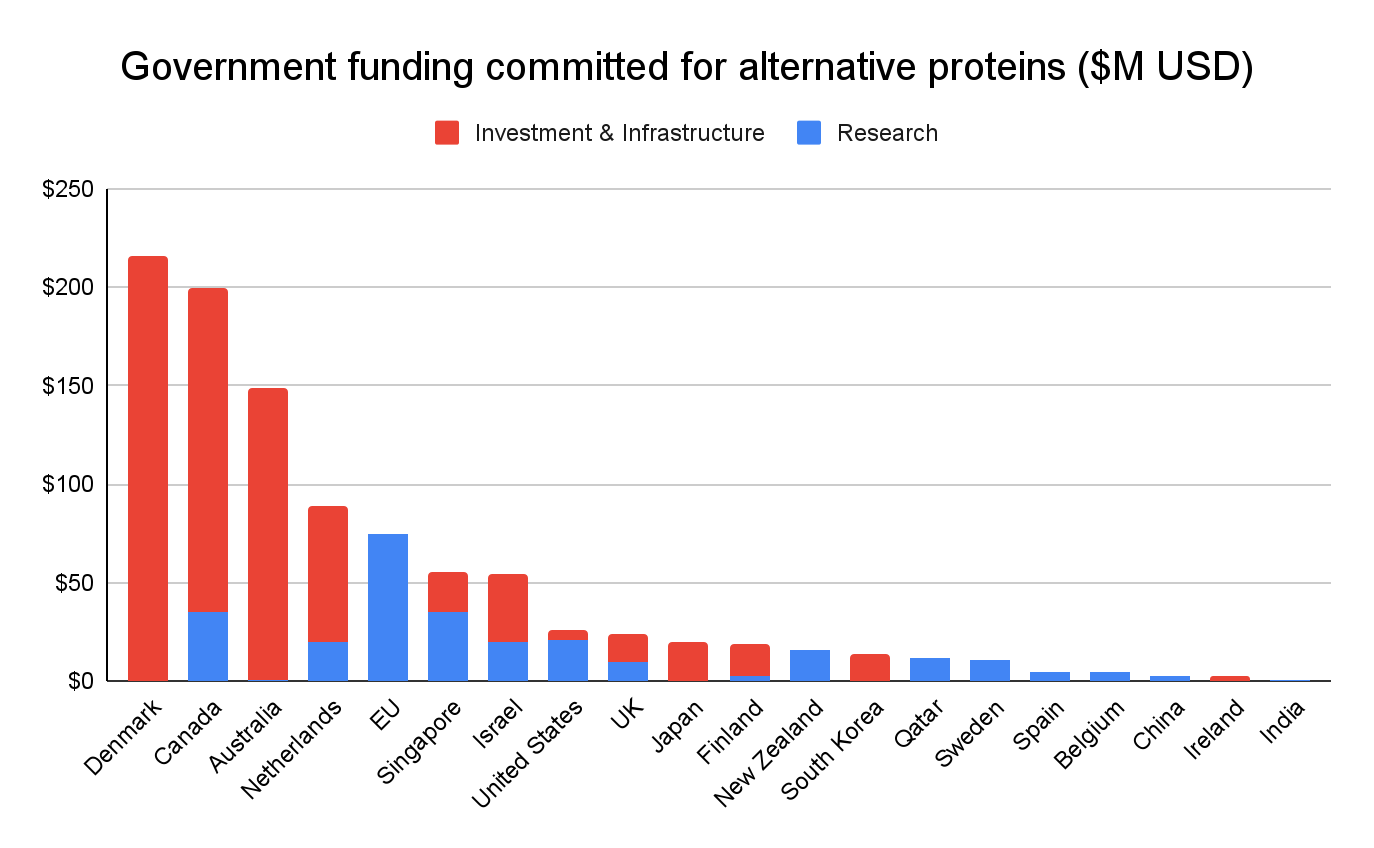

In order to effectively address these bottlenecks, there is a need for (1) increased (public) funding for R&D and (2) upscaling of manufacturing capacity for alternative proteins, as well as (3) a supportive regulatory framework that will facilitate market authorization. Although the Dutch €60 million investment in cellular agriculture may represent the largest single investment in this space by any government worldwide, it is negligible compared to government funding in other areas, such as renewable energy. Current levels of public funding are still below those justified by the scale of moral, environmental, and even economic benefits of alternative proteins. The same is true for EU funding. While significant EU funds are currently being directed towards addressing climate change and supporting traditional agriculture, the EU’s Horizon program has allocated relatively negligible funding for alternative proteins [18]. In 2021 and 2022, the EU invested only €32 and €25 million respectively in the sector. These figures are negligible compared to the tens of billions spent on research annually [19]. To realise the potential of alternative proteins, there is a need for increased public funding both at the (Dutch) national level and at the European Union level.

Figure 2: Government funding for alternative proteins, source: OpenPhilantropy, 2022 [20]

Furthermore, regulatory refinements in the EU are needed to enable (easier) market authorization of alternative proteins. Regulatory uncertainty remains a major obstacle for food business operators seeking to develop or produce alternative protein products in the EU. The current approval process for novel foods in the EU includes the following three rounds:

- The first round includes documentation and submission, in which the applicant provides all necessary documentation for an initial assessment to check if the application is complete. The EU does not provide clear details about what has to be in the dossier, and pre-submission consultations are not possible. There is no strict timeline for this phase, and details of the application are kept confidential.

- The second round is the safety evaluation by EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). EFSA aims to complete this assessment within nine months, providing a scientific opinion on the safety of the novel food. Based on EFSA’s positive assessment, the European Commission submits a draft implementing act proposing the authorization of the novel food to the Standing Committee on Plants, Animals, Food and Feed.

- In the third round, representatives of the Member States in the Standing Committee vote on the approval of the product. In order to authorise the novel food, at least 55% of the Member States representing at least 65% of the EU population must vote in favour.

Career paths

The Alternative Protein industry is rapidly growing with a diverse range of roles and skills in high demand. These include (1) policy and advocacy, (2) research and development, and (3) business and entrepreneurship. Skills from nutrition, consumer science, sustainability, marketing and technology sectors are increasingly valuable as this movement grows.

1. Policy and Advocacy

Engaging in policy or advocacy for alternative proteins, especially in securing more funding and refining the regulatory framework, is potentially one of the highest impact career paths in the sector. By increasing funding and supportive regulations, the development and market authorization of alternative proteins can be expedited. Potential career paths are outlined below.

Lobbying

A career in lobbying for alternative proteins involves actively advocating for policy changes and increased funding at the national or EU level. Engaging in lobbying for alternative proteins in the European Union can be especially impactful, potentially more so than at national levels. This is because the EU is the source of many overarching regulations and directives that member countries must follow. Lobbyists focus on influencing lawmakers and stakeholders to support the development and market authorization of alternative proteins. Currently, there are only about 15-40 full-time equivalents (FTE) lobbying for alternative proteins in Brussels. This suggests a substantial opportunity for increased impact by boosting these numbers. Key advocacy groups in Brussels include:

- Well established climate NGOs could be influenced to shift their focus and lobbying more towards alternative proteins. Some Dutch (based) organisations include:

- Consumer and retail organisations could be strategic options for advocacy because they are important for the EU and most of them maintain a neutral stance on alternative proteins.

- The Good Food Institute Europe (GFI Europe): International nonprofit and think tank helping to advance alternative proteins.

- SustainablePublicAffairs: Lobbying firm that specialises in influencing European policy to support sustainable innovations, including alternative protein sources.

- Food Fermentation Europe: Industry alliance for the food fermentation sector.

- Cellular Agriculture Europe: Coalition of food companies in the cellular agriculture sector.

- European Plant-Based Foods Association (ENSA): Represents the interests of plant-based food manufacturers in Europe.

If you’re interested in a career in lobbying for alternative proteins, good steps to get there are:

- For students or early career professionals: send out open applications for an internship to relevant organisations. Building up experience in how Brussels (or the national context in which you’re lobbying) works is crucial.

- For mid-career professions: look out for vacancies from relevant organisations.

- In general, build up relevant knowledge, skills, and experience such as:

- Understanding of the political landscape: A comprehensive knowledge of the political environment, especially in relation to food policy and sustainability, is essential. This includes awareness of current debates, policy trends, and the ability to anticipate how changes in the political landscape could impact the alternative proteins sector. Following POLITICO’s EU Confidential podcast and Neth-er newsletter are good starting points.

- Industry-specific knowledge: Familiarity with the alternative proteins sector, including trends, challenges, and key players.

- Experience in EU institutions: Familiarity with the workings of EU institutions such as the European Parliament, European Commission, and European Council is vital if your lobbying is focussed on the EU. Experience in these institutions provides a solid foundation for understanding legislative processes and regulatory frameworks within the EU.

- Networking skills: Strong networking skills are crucial for building a web of contacts in the industry. Attend relevant events, conferences, and meetings to build relationships with policymakers and industry stakeholders.

- Advocacy and persuasion skills: Strong communication skills, both written and verbal, and the ability to present compelling arguments are necessary in successfully advocating for policy changes and persuading stakeholders.

Research behind lobby work

A lot of research is needed behind effective lobby efforts. A career in research to support lobbying efforts typically involves conducting in-depth research and analysis on various aspects of the industry, including market trends, technological advancements, environmental impact, and regulatory landscapes. Professionals in this field often work at the same organisations involved in advocacy (some of which listed above) but focus more on gathering and synthesising data to inform lobbying strategies, rather than direct persuasion. Key responsibilities include developing white papers, policy briefs, and reports that provide evidence-based insights to support lobbying efforts. If you’re interested in a research role to support lobby efforts, good steps to get there are:

- For students or early career professionals: send out open applications for an internship to relevant organisations to build up experience and network.

- For mid-career professions: look out for vacancies from relevant organisations.

- In general, build up relevant knowledge, skills, and experience such as:

- Research skills and strategic thinking. In certain research roles, having a PhD can be a benefit.

- Understanding of the political landscape. A comprehensive knowledge of the political environment, especially in relation to food policy and sustainability, is essential. This includes awareness of current debates, policy trends, and the ability to anticipate how changes in the political landscape could impact the alternative proteins sector.

- Industry-specific knowledge. Familiarity with the alternative proteins sector, including trends, challenges, and key players.

Civil servant EU/member state

The role of an EU Policy Officer is centred around engaging with the complexities of EU food regulation and agricultural policy. This position offers the opportunity to delve into the intricacies of how food policies are shaped and implemented across the European Union. Different career paths within the EU include:

- Work at the European Commission, which allows for direct involvement in proposing and shaping EU legislation. The European Commission is organised into several policy departments known as Directorates-General (DGs), each responsible for specific policy areas. These DGs develop, implement, and manage EU policy, law, and funding programs. Each DG is headed by a Commissioner who is part of the College of Commissioners, guiding the Commission’s political and strategic direction. As a policy officer, you can aim to work at a relevant DG for the alternative protein sector, such as:

- DG Research and Innovation (RTD): Focusing on research and innovation aspects of agricultural policy.

- DG Agriculture and Rural Development (AGRI): Centrally involved in developing and implementing EU agricultural policies.

- DG Health and Food Safety (SANTE): Responsible for overseeing EU policy on food safety and health, ensuring the implementation of related laws and the safety of Europe’s food supply.

- Work at EU Member state governments: Working in national government bodies that deal with food safety and agricultural policy can also provide a platform to influence EU-level policy, especially through participation in EU Council meetings and committees.

If you’re interested in a career as a civil servant for alternative proteins, good steps to get there would be:

- For students and early-career professionals: Gaining entry into the field can be effectively initiated through the Bluebook Traineeship, which offers practical experience and insight into the workings of the EU. Alternatively, a national-level traineeship, such as the Rijkstraineeship, provides a solid foundation and exposure to the intricacies of EU policy at a national level.

- For mid-career professionals: Those with more experience can explore opportunities as a contract agent through the CASTsystem. This path offers temporary positions within EU institutions. Alternatively, the Concours, a competitive examination process, presents a traditional route for those seeking a long term career in EU institutions, particularly for specialised roles.

Politics

Working within politics also presents an avenue to advance alternative proteins.

- At the EU level, this could involve serving as an assistant to a member of the European Parliament. In this role, you can influence policies and legislations regarding alternative proteins, contributing to discussions and policy development. Relevant parliamentary committees are:

- The Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development (AGRI): This committee is a major player in shaping the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), as well as policies related to animal health and welfare, and quality of agriculture. AGRI is involved in preparing reports for legislative proposals under the co-decision procedure between the Parliament and the Council.

- The Committee on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI): ENVI is responsible for improving food information for consumers, notably through the regulation of labelling and the placement of products on the market. This committee’s role is critical in shaping policies and regulations related to food safety, including those governing novel foods.

- Similarly, at the national level, becoming an assistant to a member of a national parliament offers a chance to shape and drive the agenda for alternative proteins within a specific country.

2. Research and Development

Career paths in research and development of alternative proteins are usually within academia, start-ups/companies, or think tanks. There is a broad range of important research needed on alternative proteins, including: their development, their health and environmental effects, consumer acceptance, and policy analysis.

Academia

Pursue a PhD or work in a postdoctoral position that focuses on food technology, nutrition, biochemistry, or related fields. A focus on consumer behaviour and acceptance of novel foods could also be important. Focusing on interdisciplinary approaches that blend biotechnology, food science, and sustainability studies can be particularly beneficial. In the Netherlands, several universities and research initiatives are actively involved in the field of alternative proteins. If you’re aiming for a (research) career in alternative proteins, getting a relevant degree at Wageningen University and Research (WUR) is probably your best choice. WUR is a globally leading university in agricultural, food, and environmental sciences. In the Netherlands, WUR is a leading institution in alternative proteins research. Other universities that offer a strong foundation are: TU Delft, Utrecht University, Maastricht and Leiden. Here are some of the notable programs and initiatives from Dutch universities:

- Protein Transition Consortium: This consortium comprises Dutch universities (including TU Delft and WUR), companies, and organisations dedicated to understanding and accelerating the transition to plant-based proteins. They approach the protein transition from various perspectives, including consumer motives for dietary shifts and strategies for promoting plant-based diets.

- WUR – Proteins for Life: This program aims to shift protein production and consumption, focusing on more sources like legumes, aquatic crops, and insects to tackle the issues of malnutrition and environmental impact caused by current agricultural practices. The program focuses on developing protein-rich products with scientifically based health effects and quantitative understanding of the sustainability of proteins and the motivation of consumers to opt for plant-based products.

- WUR – Protein Transition Movement: Research emphasising the need for a sustainable, equitable, and balanced protein system and are actively seeking ways to increase the availability, diversity, and acceptance of both existing and new protein sources. It’s an initiative that highlights the WUR’s commitment to developing sustainable food sources.

- WUR and Utrecht University have active student groups on alternative proteins [21][22] .

New Harvest sometimes provides various types of financial support for researchers in the field of cultivated meat, including research fellowships, seed grants, and dissertation awards. They fund research projects and educational opportunities that train students in the skills required to grow meat from cells [23].

Start-ups/companies

Working within an alternative proteins startup or company offers a dynamic and innovative environment where a growing number of roles and the skills are needed. The potential roles and specific skills required depend on various factors, such as the stage of the start-up (e.g., early-stage vs a new alternative protein branch in an established corporation), the technology used (plant-based, fermentation, cultivated meat, hybrid), and the go-to-market strategy [24]. Crucial career paths include:

- Research science.

- Product developing: Design and refine alternative protein products to meet consumer needs and preferences, focusing on taste, texture, and nutritional value.

- Process engineering: Specialise in scaling up production processes from the lab to commercial production.

In the early stages, start-ups typically hire their core team, including management and key roles like the Chief Scientific Officer. These roles are often recruited directly by the (co-)founders. When a start-up has gone through one or two funding rounds, they usually rapidly expand their team with multiple positions opening up simultaneously. If you’re looking for a career in this space, the end of a funding round is a good opportunity to look for potential job openings. More established startups and larger companies, on the other hand, have more formal and structured recruitment processes. These are usually handled by their HR departments or through external recruitment agencies. Some key skills essential in startups or companies in this sector include [25]:

- Knowledge of biology, chemistry, and biochemistry: Working with alternative protein products requires a strong foundation in scientific knowledge and hard skills, as well as a deep understanding of complex processes. It is essential to have a thorough understanding of biology, chemistry, and biochemistry in order to successfully develop and work with these products, which may be derived from various biological sources such as plants and microbes.

- Engineering and manufacturing expertise: Alternative protein products are typically produced using novel technologies, so expertise in engineering and manufacturing is important for ensuring that these products are made efficiently and to high standards.

- Food science and nutrition: Alternative protein products must meet the same safety and quality standards as traditional protein sources, so knowledge of food science and nutrition is important for developing and producing these products.

- Flexibility/entrepreneurial spirit: Positions in start-ups often require a blend of technical expertise and entrepreneurial spirit.

Think tanks/Research institutes

Think tanks and research institutes in the alternative protein sector are dedicated to researching and advocating for sustainable protein sources, such as plant-based, cultured meat, and fermentation-derived proteins. They operate at the intersection of science, policy, and industry, providing evidence-based insights and recommendations to policymakers, industry leaders, and the public. Professionals in these organisations typically engage in:

- Research and analysis: Conducting comprehensive studies on market trends, technological advancements, and policy impacts in the alternative protein sector.

- Policy advocacy: Developing and promoting policy recommendations to support the growth of the alternative protein industry.

- Communication and outreach: Spreading research findings and policy proposals to a wider audience, including through reports, conferences, and media engagement.

Some notable Dutch or European think tanks and research institutes on this topic are:

- Good Food Institute Europe (GFI Europe): a leading think tank and policy advocacy group promoting alternative proteins in the EU.

- The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (HCSS): a Dutch think tank exploring various global issues, including sustainable food security. Their research often touches on the implications of alternative protein sources in the context of global food systems.

- TNO: a Dutch research institute conducting applied research and offers advice on various topics, including sustainable food production and technology, which encompasses alternative proteins.

3. Business and entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurs and business professionals in this domain are tasked with the challenge of navigating a rapidly evolving landscape, identifying niche markets, and scaling innovative products. They must have a keen eye for emerging trends and an understanding of relevant regulatory environments. Relevant career paths include:

- Marketing and sales: Work in a company/start-up to understand consumer behaviour, create compelling narratives around alternative protein products, and develop strategies to bring them to market. As the alternative protein industry grows, there’s also a growing need for adept marketing professionals to shape perceptions and convey the benefits of these novel food sources to the masses.

- Business development and strategy: Work in a company/start-up to identify market opportunities, build partnerships, and create long-term strategies to help alternative protein companies grow and succeed. The alternative protein industry is a rapidly changing and competitive field, so business development and strategic thinking skills are important for helping companies navigate this environment.

- Founding a start-up: Found an alternative protein start-up. This requires not just technical knowledge but also entrepreneurial skills to secure funding, market the product, and manage a growing business. This career path is extremely important to the sector but has a higher risk.

- Consulting: Use your knowledge of the alternative protein industry to advise existing companies on market trends, regulatory issues, and business strategies.

Find opportunities on the job board

- Tälist job board

- Alt Protein Careers job board

- GFI Talent Database

- European Commission Blue Book traineeships

Learn more

Courses & career tools

- GFI: Open-access Online Course

- GFI: Student Resource Guide

- Charity Entrepreneurship: Incubation Program

- BlueDot Impact: Alternative Protein Fundamentals Course

- CellAg Australia: CellAg Pathways Tool

- Soon to be launched: Tälist careers in alternative protein course

Who is working on this problem?

- See KET maps for a visual representation of the landscape.

- See Protein Directory for a company database.

Networking and community

Conferences & Events

- GFI: Community

- GFI: Events

- GFI: Workshops

- ProVeg: New Food Conference

Newsletters & magazines

- Food Hack Global: Newsletter

- The Future Of Protein Production: Magazine

- Vegconomist: Magazine

- Good Food Institute: Newsletter

- Tälist’s starter’s guide to alternative protein career: Blog

Podcasts

- Cultivating Careers in Alternative Proteins: Podcast

- FoodUnfolded: Podcast

- Red To Green: Podcast

- 80,000hours: Podcast

Beyond your career

The possibilities for helping advance alternative proteins don’t end with your career choice. As a citizen, the potential for influence extends beyond your job title.

- Contributing financially to the Good Food Institute (GFI) is a very effective way. GFI is rated as a top-charity by Animal Charity Evaluators and Giving Green.

- Increase demand for alternative proteins by your consumption patterns.

- As of now, Dutch political parties haven’t clearly defined their positions on alternative proteins. However, for those interested in this issue, it might be wise to consider voting for parties that generally prioritise animal welfare. Such parties are more likely to support initiatives aligned with the development and promotion of alternative proteins.

Footnotes

- https://www.founderspledge.com/research/animal-welfare-cause-report

- https://ourworldindata.org/how-many-animals-get-slaughtered-every-day

- https://www.shrimpwelfareproject.org/

- https://www.speciesunite.com/podcast/melanie-joy

- https://www.sentienceinstitute.org/global-animal-farming-estimates

- https://www.effectivealtruism.org/articles/cause-profile-animal-welfare

- https://animalcharityevaluators.org/donation-advice/why-farmed-animals/

- https://www.unep.org/resources/whats-cooking-assessment-potential-impacts-selected-novel-alternatives-conventional

- https://ourworldindata.org/greenhouse-gas-emissions-food

- https://ourworldindata.org/agricultural-land-by-global-diets

- https://gfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/GFI-Fact-Sheet_-Alternative-Proteins-Address-the-Threats-of-Antibiotic-Resistance-and-Pandemics_POL22023.pdf

- https://www.wri.org/insights/how-sustainably-feed-10-billion-people-2050-21-charts#:~:text=Consumption%20of%20ruminant%20meat%20,as%20beans%2C%20peas%20and%20lentils

- https://gfi.org/defining-alternative-protein/

- https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/per-capita-meat-consumption-by-type-kilograms-per-year

- https://www.emergingproteins.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/EPNZ-Sept-2022-Report-WEB2.pdf

- https://www.emergingproteins.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/EPNZ-Sept-2022-Report-WEB2.pdf

- https://www.emergingproteins.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/EPNZ-Sept-2022-Report-WEB2.pdf

- https://gfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/GFI-Blueprint-v.8-Oct-2022.pdf

- https://www.climateworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/GINAs-Protein-Diversity.pdf

- https://www.openphilanthropy.org/research/how-can-governments-advance-alternative-proteins/

- https://gfi.org/directory/the-wageningen-alt-protein-project/

- https://gfi.org/directory/the-utrecht-alt-protein-project/#:~:text=,development%20hub%20on%20alternative%20proteins

- https://new-harvest.org/what-we-do/

- https://talist.org/talent-resources

- https://talist.org/talent-resources